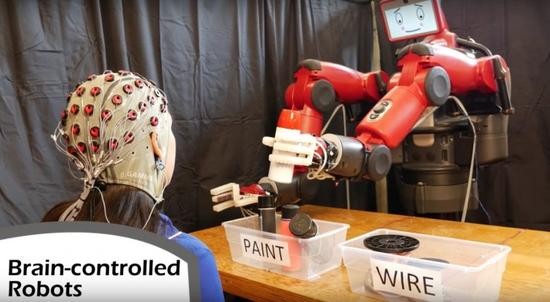

For the robot to do what we want to do, they need to understand our commands. In the vast majority of cases, this means that we have to compromise with them: for example, to teach them the intricate human language, or to give them clear commands to accomplish very specific tasks. But what if we could develop a robot that was like a part of our body and could do whatever we wanted to do? A team from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) and Boston University is working to solve this problem and create a feedback system that allows people to correct robot errors immediately using their brains. The feedback system developed at MIT allows human operators to correct the choices made by the robot in real time using only brain signals. Using data from an electroencephalogram (EEG) monitor that records brain activity, the system can detect whether a human has noticed an error made by the robot when performing an object classification task. The team's new machine learning algorithm enables the system to identify classified brain waves in 10 to 30 milliseconds. Although the system currently only deals with relatively simple binary selection problems, the authors of this article say that this study shows that one day we can control the robot in a more direct way. “Imagine being able to immediately tell the robot to complete a specific action without having to type a command, press a button or even say a word,†said CSAIL Director Daniela Rus. “This simple approach will enhance our ability to oversee factory robots, driverless cars, and even other technologies that we have not invented yet.†In the current study, the team used a humanoid robot called "Baxter" from RethinkRobtics, which was led by former CSAIL director and iRobot co-founder Rodney Brooks. The paper introducing this work was written by Dr. AndresF. Salazar-Gomez, Dr. CSAIL candidate Joseph DelPreto and CSAIL research scientist Stephanie Gil at Rus and BU Professor FrankH. Written under the supervision of Guenther. The paper was recently included in the IEEE International Robotics and Automation Conference (ICRA) in Singapore in May this year. In the past, EEG's work in controlling robots required trainers to "think" in a prescribed way that computers can recognize. For example, an operator may have to view one of two highlight displays, each of which displays a different task performed by the corresponding robot. The disadvantage of this approach is that the training process and the process of adjusting one's own ideas are cumbersome and tiring, especially for those who supervise navigation tasks or those who need a highly concentrated construction industry. Rus' team wants to make the experience more natural. To do this, they focus on brain signals called "error-related potentials" (ErrPs), which are produced when the brain notices an error. When the robot selects as directed, the system uses ErrP to determine if the operator agrees to the decision. "When you look at the robot, all you have to do is mentally agree or disagree with what it is doing," Ruth said. "You don't have to train yourself to think in some way, it's the machine that adapts to you, not the other way." The ErrP signal is very weak, which means that the system must be fine-tuned to classify the signal and use it in the operator's feedback loop. In addition to monitoring the initial ErrP, the team also tried to detect "secondary errors" that occurred when the system did not notice the person's initial decision. "If the robot is unsure of its decision, it can trigger a human response and get a more accurate answer," Gill said. “These signals can significantly improve the accuracy of the selection and communicate by establishing a continuous dialogue between humans and robots.†Zhuhai Mingke Electronics Technology Co., Ltd , https://www.mingke-tech.com