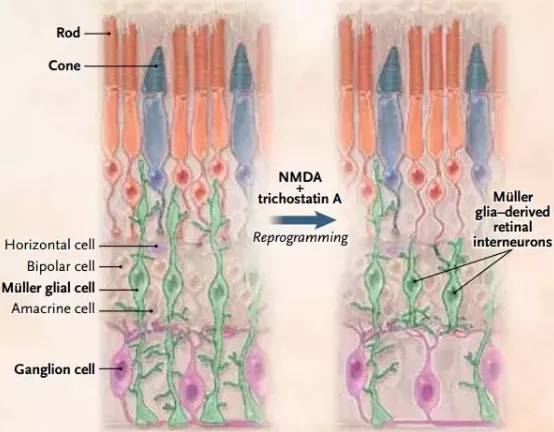

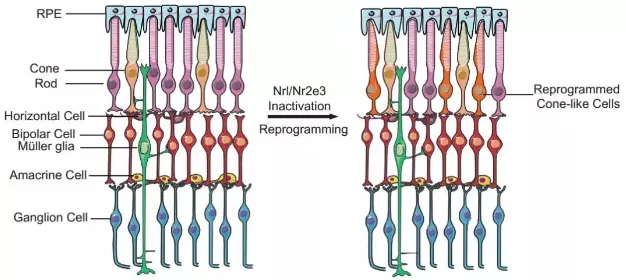

Release date: 2018-03-21 Not long ago, the research of the team of Professor Zhang Kang of the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) was published on the cover of Cell magazine, bringing patients an artificial intelligence algorithm that can accurately diagnose multiple diseases. Recently, Professor Zhang Kang and Prof. Lu Wei, Dean of the Institute of Ophthalmology, Eye and ENT Hospital of Fudan University, once again published articles in top academic journals in the latest issue of the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). On the other hand, Prof. Lu Wei and Professor Zhang Kang gave a detailed introduction to the recent progress in reprogramming retinal cells for regenerative therapy. Professor Zhang Kang (left) and Professor Lu Wei (right), author of this study (Source: UCSD / Fudan University) 1. Why do mammals lack regenerative capacity? The retina is vital to human vision. According to statistics, there are currently more than 50 million patients worldwide suffering from irreversible blindness, and the most important cause is the deterioration of retinal neurons. Therefore, finding a way to delay or even reverse the process of degradation has become the direction of the current researchers. In invertebrates, researchers have seen hope – in the case of fish, when their retina is damaged, it initiates the process of “dedifferentiation†and “cell reprogramming†to make endogenous Müller colloids. Cells (Müller glia) proliferate and differentiate into many different types of retinal cells, reshaping vision. If you can reproduce this process in the body of patients with eye diseases, can they restore their vision? not that simple. Compared to fish, mammals have almost zero regenerative capacity. Want to reproduce, how easy is it? Experimental results in fish cannot be easily replicated in mammals (Source: By Oregon State University (Zebrafish) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], Via Wikimedia Commons) Further research in fish gives us a deeper understanding of the molecular mechanisms behind regenerative capacity. In order to dedifferentiate and reprogram Müller glial cells into retinal neurons, specific genes need to be reactivated. This is similar to the genes required for activation of retinal pluripotent progenitor cells into retinal neurons during embryonic development. This discovery has brought new inspiration to researchers. They found that after the zebrafish's retina was damaged, a transcription factor called Ascl1 was up-regulated in Müller glial cells, which is necessary for retinal regeneration. When the mammal's retina is damaged, Ascl1 is not expressed. Is this the key to the difference in regenerative capacity between fish and mammals? 2. Breakthrough in retinal regeneration To test this idea, the team of Professor Thomas A. Reh of the University of Washington in the United States used genetic engineering to allow mice to express Ascl1 in Müller glial cells. This seemingly simple experiment has had a gratifying effect – the expression of Ascl1 stimulates regeneration of retinal nerve cells, both in vitro and in vivo. At first glance, we have mastered the key to promoting retinal regeneration in mammals. But the good times are not long. The researchers quickly discovered that even if Ascl1 is in persistent overexpression, this regenerative capacity will still disappear on day 16 after birth. This suggests that Ascl1 is not the only key element of retinal regeneration. With the decline in regenerative capacity, the chromatin "accessibility" of Müller glial cells is also reduced, which means that the expression of many genes required for regeneration may be inhibited, and epigenetic regulation is behind it. Graphic of the study (Source: "NEJM") In order to overcome this obstacle, the researchers decided to use a genetic modification method to improve the expression of Ascl1 in Müller glial cells, and on the other hand, epigenetic injection of histone deacetylase in these cells. Agents, many transcription factors including Ascl1 can better promote the expression of downstream genes. The results, as the researchers expected: improved, the efficiency of these Müller glial cells into retinal neurons has been greatly improved, and the differentiated retinal neurons can form synapses with existing neurons, integrating In the neural circuit of the retina, and with the stimulation of light, a potential is generated. In other words, these newly formed cells have normal physiological functions. The study was recently published in Nature. Professor Lu Wei and Professor Zhang Kang pointed out in the review that this study has important direct medical value. In general, in situ cell reprogramming in vivo has a lower risk of infection or rejection than conventional stem cell therapy. The possibility is also smaller. In the treatment of ophthalmic diseases, if this regenerative therapy can be verified and promoted in the human body, the photoreceptor cells and retinal ganglion cells are induced in the patient's eyes, which will be a great boon for the patients. 3. Prospects for cell regeneration therapy The review also points out that, in a broad sense, cell regeneration therapy is expected to treat severe eye diseases including retinitis pigmentosa and macular degeneration in a subtle way – retinitis pigmentosa is a very diverse genetic disease. The cause can be traced back to more than 200 different genes and tens of thousands of mutations. If one-by-one gene therapy is designed to correct each mutant gene, even if it is feasible, the efficiency is extremely low and the cost is too high. In 2017, Professor Zhang Kang's team published a paper on Cell Research, which introduced its latest method of gene editing to treat all patients with retinitis pigmentosa. The researchers pointed out that genetic mutations that cause retinitis pigmentosa mainly affect rod cells. After causing these cells to degenerate and lose function, they further affect the cones, resulting in decreased vision accuracy and poor color perception. Interestingly, there are far more rods in the human body than cones. It is estimated that there are about 6 million cones in the retina, and the number of rods is as high as 120 million, which is 20 times that of the former. Using the CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technology, Professor Zhang Kang successfully knocked out the Nrl and Nr2e3 genes in the rod cells. As a "switch" that controls cell fate, Nrl and its downstream transcription factor Nr2e3 promote the differentiation and formation of rod cells. Once these genes no longer function, the rod cells can become cones. In theory, although these cells still carry mutations that cause retinitis pigmentosa, because cones are not susceptible to these mutations, mutations can be "invalidated" to maintain tissue function. The sheer number of rod cells also minimizes the impact of cell type changes. Mouse experiments validate the feasibility of this idea (Source: Precision Clinical Medicine) In animal experiments, the researchers used two different models of mouse retinitis pigmentosa to verify the feasibility of this idea. The study found that under the action of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technology, with the "inactivation" of the Nrl and Nr2e3 genes, a large number of rod cells were reprogrammed into cone cells and maintained the normal cellular structure in the retina. The electroretinogram test further showed that the electrophysiological function and visual acuity of the mice did improve significantly. "Another benefit of in-situ cell reprogramming is that there is no need to introduce external cells. Just as it is easy to damage plants with flowers and plants, externally transplanted cells may not be able to adapt to the new environment," Professor Zhang Kang commented. Dao: "But the in-situ cell reprogramming technique is different. The newly-converted cone cells grow and grow in their own retinas, adapt to the surrounding environment, and are not acclimatized." Of course, there are still many ways to go before regenerative therapy goes to ordinary patients. Due to the uniqueness of the human retinal structure, we need to test the safety and efficacy of this therapy in a primate model before human clinical trials. Fortunately, it is understood that Professor Zhang Kang’s team has been tested in a primate model with good safety and effectiveness. Clinical trials are expected before the end of 2018. In 2017, we welcomed the first CAR-T therapy and the first human gene therapy. We also look forward to seeing a breakthrough in ophthalmology in the near future. Whether it is for researchers or patients, the front is full of light! References: 1) Lu Y and Zhang K, Cellular Reprogramming in the Retina — Seeing the Light. NEJM 2018 2) Jorstad NL, Wilken MS, Grimes WN, et al. Stimulation of functional neuronal regeneration from Müller glia in adult mice. Nature 2017;548:103-7 3) Zhu J, Ming C, Fu X, et al. Gene and mutation independent therapy via CRISPR-Cas9 mediated cellular reprogramming in rod photoreceptors. Cell Res 2017;27:830-3. Source: Academic Jingwei Rapid H.pylori Ag Test Kit (Colloidal Gold) H.pylori ,H.pylori Ag,Antigen,Colloidal Gold,Test Cassette Shenzhen Uni-medica Technology Co.,Ltd , https://www.unimed-global.com